Cherie Nicoletta couldn’t speak when she tried to call her son in mid-June last year. Two weeks earlier, she had been diagnosed with COVID-19. She was staying in a hotel through Vallejo’s Project RoomKey program – intended to help medically vulnerable people experiencing homelessness stay safe during the pandemic – and was quarantined in her room.

In the call to her son’s partner, Nicoletta moaned as if she was in pain but said nothing. Her son, Robbie Perry, rushed to the hotel to check on her.

When Perry got to the Hampton Inn, the electronic room key his mother had given him didn’t work. Security guards at the hotel tried to open the door, but they couldn’t get in either and told Perry to come back three days later, on Monday. Concerned his mother was having an emergency, Perry looked into ways to break the lock. But when he returned over the weekend, a worker at the hotel told him his mother was back in the hospital.

Perry contacted every hospital in the area, but none said they had admitted his mother. He called the Vallejo Police Department, but they were no help either. Perry returned to the hotel once again on Monday, where he met Kevin Sharps, head of Project RoomKey’s case management.

According to Perry, Sharps brought him to the room and asked him if he was “ready” for him to open the door.

Perry walked in and saw his mother on the floor, where she had been dead for days.

Nicoletta was at least the fourth person who died in Vallejo’s Project RoomKey program since it began in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two other people who died before her were also not found for days.

In a series of interviews, family members of those who died and former Project RoomKey residents in Vallejo described neglect by program staff. They say that conditions at the hotels under Project RoomKey were filthy, with trash piled outside of doors and feces left in the halls for days.

One motel the city used had an extensive mold infestation, records show. An inspector the city hired documented it weeks after a woman with a chronic lung disease died there. A city contractor said the city intended to buy the motel but later abandoned that plan.

The city has refused to answer direct questions about the deaths, including whether the four discovered by the Vallejo Sun represent a full accounting of Project RoomKey residents who died. Each of those deaths triggered a police investigation, but if a resident was taken to a hospital before they died, there would be no investigation.

The program was run by a piecemeal network of providers, who either worked for the city or county or were contracted by the city to run various aspects of the program. One was Unity Care, a San Jose-based organization that primarily provided housing and other services for foster kids, which the city has credited with operating much of the program. Sharps is the Vallejo program director for Unity Care.

Six weeks after Nicoletta died, Vallejo Mayor Robert McConnell praised Project RoomKey as an unmitigated success in a Facebook post. “Congratulations Unity Care on a job well-done,” McConnell wrote. He did not respond to questions about the post and whether he was aware of the deaths at the time.

But Unity Care said that its role in the program was limited to case management. In a statement to the Vallejo Sun, Tatiana Colon Rivera, Unity Care’s director of strategic partnerships, said that staff were not present on weekends and they weren’t responsible for property management. “Property management and janitorial was the responsibility of the City at both facilities, through the property owners at the Rodeway and directly at the Hampton,” Colon Rivera wrote in an email.

In 2019, the state Department of Social Services moved to revoke Unity Care’s license for foster care homes it operated in the Bay Area. State records indicate that similar conditions were reported in homes as residents and family members described in Project RoomKey. The state found that children were left unattended and conditions were not safe or sanitary.

‘The system failed her’

Cherie Nicoletta was born in Utica, New York, but when she was young her family relocated to Green Valley, California, where she grew up, according to her daughter, Alyssa Borrilez. Fun and gregarious, she enjoyed water skiing, horseback riding, and dressing up. In high school, Nicoletta was homecoming queen.

“She had really great taste and great style,” Borrilez said.

After graduating high school, Nicoletta sought to travel, so she got a job as a flight attendant, a role she worked in for decades.

Nicoletta also struggled with bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Borrilez recalled that in her early childhood her mother had been to rehab. But by the time Borrilez entered school, her mother was sober, had bought a home and was working. Nicoletta reconnected with a high school boyfriend, they married and the family moved to Benicia.

In her early 40s, a series of problems in Nicoletta’s life led to a decline in her mental health. “Her father died and she was going through a painful divorce,” Borrilez said. “What came first, mental health issues or substance abuse, I don’t know.”

“It all happened really fast,” Borrilez said. “The next thing I knew, I was staying at an aunt's house and my brother was at my dad’s.”

Nicoletta retired early as a flight attendant after failing a drug test, Borrilez said. She received social security and some retirement benefits from her airline, but it wasn’t enough to afford housing and food. She received benefits through the Section 8 housing voucher program but was evicted for manic behavior. “And then they pulled her voucher,” Borrilez said, “so she decided to live in her car.”

“The system failed her,” Borrilez said. “I think she just had very bad mental health and no resources to turn to.”

Nicoletta lived in her car at various places in Vallejo. As her children grew up, they did whatever they could to help her, but she often refused to take their assistance. “She was never like, ‘Can I come live with you?’” Borrilez said. “In fact, it was always like, ‘What do you guys need? Can I do something for you? Do you need anything? Do you need money?’ I was always like, ‘No, you’re living on the street. I can’t take your money.’”

But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March 2020, Borrilez was more afraid for her mother than ever. Borrilez was living in Los Angeles by then and had recently had a baby, so couldn’t even offer what little help her mother would accept. But Nicoletta discovered Project RoomKey and was accepted into the program, which was a relief for Borrilez.

Borrilez said she thought, “Oh, thank God. You have a room, you can shower. You can bring food there.”

Nicoletta moved into the Hampton Inn across from the Six Flags Discovery Kingdom amusement park. She enjoyed the room and sent her daughter pictures of it. “She was really happy there,” Borrilez said.

‘Everybody’s got a problem here’

The pandemic left people experiencing homelessness — who often suffer from chronic medical conditions and live in congregate settings — particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. The state Department of Social Services enacted Project RoomKey to provide spaces in hotels for people who didn’t have housing but had medical issues that put them at higher risk if they contracted COVID-19.

In Vallejo, it initially operated at the Hampton Inn, where the city rented the entire approximately 100-room hotel.

The program was funded through a mix of federal, state and local funds. In Vallejo, it cost up to $650,000 per month to provide the required on-site meals, private security, and medical services, including behavioral health. Participants were referred either by city or county services or by nonprofit organizations helping people experiencing homelessness, including Caminar, Vallejo Together or Fighting Back Partnership.

In April 2020, the city contracted with Fighting Back Partnership to provide case management services for Project RoomKey. The organization’s duties included coordinating daily temperature checks and COVID-19 assessments and to check in with participants multiple times per day to identify their basic needs. The contract ended June 30, 2020. Fighting Back Partnership did not respond to questions about its role or why it did not continue to participate in Project RoomKey.

That July, residents were moved from the Hampton Inn to the Rodeway Inn, a two-story residential motel near Interstate 80. Nicoletta complained about the conditions at the Rodeway early on. In a July 13, 2020, voicemail, she told her daughter, “Right now, I'm in a lockdown here at the hotel. The one they brought us to, which is the biggest fucking dive I’ve ever been in.”

“Both my lamps don't work, no light in the bathroom. No hot water, paint on the floor,” Nicoletta said in the voicemail. “They’re being really strict. They want us to stay in place, but that doesn't work in here. The TVs don't work. It's just one thing after another. The only thing that does work is the air conditioner and the phone. So yeah, we're gonna have a real big problem here. They’re probably gonna have to move us all.”

“From what I hear, everybody's got a problem here,” she said. “There's something wrong in every single room.”

‘Remarkably successful’

The city of Vallejo entered a one-year contract with Unity Care to provide services for Project RoomKey in October 2020. The contract, signed by Unity Care CEO Andre Chapman, states that Unity Care would provide case management services to Project RoomKey participants and, starting on Dec. 1, 2020, would provide property management services at the Rodeway Inn.

The provisions of the contract for case management included to “check in with Participants multiple times per day to identify any basic need,” keep a 24-hour emergency phone for any case management emergencies, and keep a staff member on call at all times.

According to Unity Care, the property management portion of the contract never took effect and was contingent on the city purchasing the Rodeway Inn, which did not happen. The contract does not explicitly say that the agreement is predicated on the purchase.

“The City's negotiation with the property owners failed and the anticipated purchase did not materialize,” Unity Care’s Colon Rivera said in an email. “Accordingly, the property management portion of the agreement between Unity Care and the City was never put into effect and Unity Care never provided property management.”

Unity Care was founded in 1992 by Chapman, who before that had worked primarily in sales for tech companies, including as a national director for sales for a software company, according to his LinkedIn profile. Nearly 30 years later, he is still CEO of the San Jose-based nonprofit.

The organization primarily provides services to foster youth. According to Unity Care’s 2021-2026 Strategic Plan, it provided housing and other services to more than 350 youth in foster care and families in 2020 and operates in nine California counties. Unity Care’s website says that it provides services to more than 7,500 youth each year, with others enrolled in other services, such as outpatient mental healthcare and independent living skills programs, which provide education to help foster youth become self-sufficient.

But recently, Unity Care has been disciplined for serious problems in its foster care facilities. In 2019, the state Department of Social Services moved to revoke Unity Care’s licenses to operate five foster facilities in the Bay Area and did not renew a provisional license for a sixth. At two facilities in San Jose, the state said staff were sleeping during their shifts. At one of those facilities, the state reported that there were holes in walls, the backyard was full of garbage, including a broken microwave, and two bedrooms did not have smoke detectors. At another facility in South San Francisco, the state described holes in walls, exposed wires, no toilet paper, and soiled furniture and floors. Unity Care admitted the allegations and surrendered the licenses.

According to Unity Care, it had not operated any other homeless shelters when it took the contract for Project RoomKey. The Vallejo project manager for Unity Care was Kevin Sharps, who was the primary manager of the organization’s role in the program. In an interview with the Vallejo Times-Herald, Sharps said he has lived in Vallejo since 2005 and became executive director of the Fighting Back Partnership in 2014. By October 2020, he worked for Unity Care.

In a video posted by Unity Care in August 2021 about a Project RoomKey vaccination event, Sharps described Project RoomKey as a place where residents were not only away from the dangers of COVID, but also thriving.

“Project Roomkey started off as a state-funded program to protect homeless citizens from the COVID virus and the program has turned out to be remarkably successful,” Sharps said. “Not only have we protected people from the COVID virus, but people have been able to find jobs, and reconnect with family and friends and do other healthy and productive things with their time here.”

But some residents in the program have described a very different experience.

'ANOTHER ONE DIED YESTERDAY’

The first confirmed death in Project RoomKey happened on Nov. 20, 2020, when 52-year-old Gary Berg Jr. was found dead in his room. A coroner’s report provided little additional information, stating that Berg had not seen a doctor in the 20 days before he died and suffered from heart disease and diabetes, identifying his cause of death as congestive heart failure.

Ten days later, 50-year-old Angie Cook was found dead. The coroner’s investigation notes that Cook had not been seen for three days before she was found.

Cook’s son, Tim Cook, later recalled that his mother was homeless off and on and suffered from debilitating medical conditions. She had seizures, breathing problems, her spine was starting to twist and she needed a second back surgery, he said. She would sometimes stay with friends but other times slept near the courthouse or City Hall in Vallejo. In 2020, she entered Project RoomKey and started staying at the Rodeway.

“It was the best thing for her,” Tim Cook said in an interview. But he wondered why the staff didn’t check in with them regularly. He said he was “kind of flabbergasted” that it appeared the staff didn’t do a daily check on residents the day after Thanksgiving “to see how everybody was doing in their rooms.”

According to the coroner’s report, Cook’s case manager, Carrie Goodspeed, checked on Cook on the morning of Nov. 30, a Monday, and found her “cold and unresponsive on her bed.” Cook suffered from hypertension, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and needed oxygen. Her doctor determined her cause of death was cardiopulmonary arrest because of her chronic condition. No autopsy was performed.

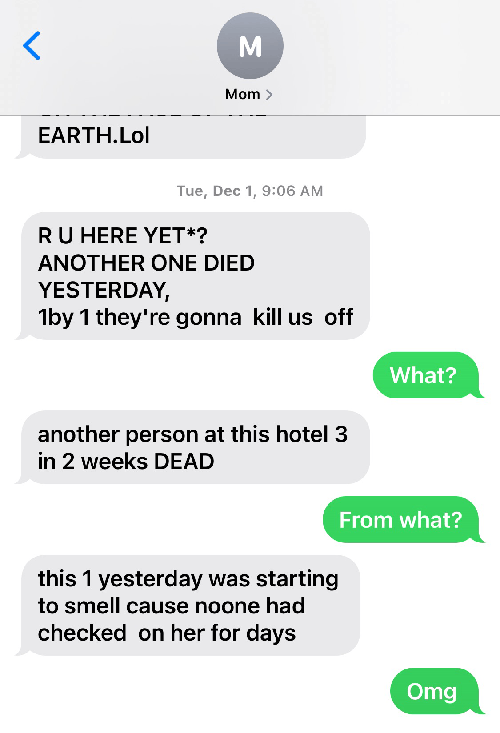

The day after Cook was found, Nicoletta texted her daughter.

“ANOTHER ONE DIED YESTERDAY,” Nicoletta wrote. “[One by one] they’re gonna kill us off.”

It is unclear who Nicoletta was referring to when she said “they’re gonna kill us off.”

“Another person at this hotel [three] in [two] weeks DEAD,” she followed up. “This [one] yesterday was starting to smell cause no one had checked on her for days.”

Borrilez said that she believed her mother may be exaggerating and didn’t follow up on the claim. While the exchange shows Nicoletta's fear after learning of Cook's death, there is no evidence that anyone involved in the program was directly responsible for any deaths.

The Vallejo Police Department only released records regarding two death investigations at the Rodeway Inn in November. However, if someone was taken to a hospital before they were pronounced dead it would not trigger a police investigation. The city declined to answer questions about how many people died in the program.

Eleven days after Cook was found dead, cleaners hired by the city did a thorough cleaning of her room, including disinfecting and HEPA-grade vacuuming. Eleven days after that, an inspector hired by the city from Express Air Testing in Burbank started an evaluation of mold growth in the Rodeway Inn.

More than 1,600 photos released by the city show that the inspector went room-to-room measuring the moisture level, photographing mold and taking samples.

Numerous photos show rooms with large black patches of mold on walls, windowsills, in the air conditioners, growing on the sides of doors and in corners of kitchens and bathrooms. Moisture readings in many of the units exceeded the top range of the instrument used.

A report by the inspectors stressed that much of the mold growth may not even be visible. “Mold infestation normally occurs within areas hidden from view (i.e. crawlspaces, ceilings, wall cavities, plumbing chases, etc.) making it difficult to locate and define all microbial contamination issues,” the report stated.

Inspectors, however, only tested samples from a single room. The results detected some spores at “major” or “abundant” levels. “At the time of this assessment there were visible signs of microbial growth, elevated moisture levels, and ambient mold spore count levels were not within acceptable limits,” the report stated.

The inspection found that humidity levels inside the Rodeway ranged between 63-64%, exceeding the 30-60% recommended for living and working spaces, placing the property at risk of microbial growth and colonization.

The remediation recommendations for the bedroom, bathroom and kitchen were for the drywall to be removed to determine the extent of mold growth. Any exposed wood or steel with mold growth should be sanded or cleaned with a wire brush. And, finally, the source of any water intrusion must be determined before anything would be replaced.

A 2004 report by the Institute of Medicine found indoor dampness and mold growth could cause or contribute to upper respiratory tract symptoms, including coughing and wheezing, exacerbate asthma, and potentially cause severe respiratory infections in some severely immunocompromised persons.

Some of the Project RoomKey participants, who were admitted to the program because of chronic medical conditions, had just the kinds of health issues that made them more vulnerable to a mold infestation.

‘The nice hotel by Marine World’

On Feb. 19, 2021, Nicoletta texted her daughter; she was excited. “Yesterday there was a note on my door, we are moving back to the NICE HOTEL by Marine World,” she wrote.

But when they returned to the Hampton Inn, the conditions there under Project RoomKey deteriorated, residents and visitors recall, with urine and feces left in hallways and elevators and trash piled outside doors.

On May 20, three months after the participants returned to the Hampton, 38-year-old Margaret Morgan was found dead in her room. According to the coroner’s report, Morgan was reported missing by her mother, who was living across the hall from her daughter.

Morgan’s mother told investigators that she had last seen her daughter on May 9, when they spent all day together. While she knew her daughter liked to keep to herself, she became concerned that she had not seen her for so long and asked hotel staff to check on her. Morgan was found unresponsive on the floor.

The coroner’s investigation was unable to determine Morgan’s cause of death because her body was so badly decomposed after being dead for days, as the Vallejo Sun reported in January.

Nicoletta’s son, Robbie Perry, visited her occasionally during her stay at the hotels. He said that he tried to check on her two or three times a week, as his work schedule permitted.

On June 1, 2021, Nicoletta was taken to a hospital for coughing, shortness of breath and chest pain. She had a fever of 102 degrees. She was diagnosed with COVID-19, according to her medical records. The hospital discharged her later in the day and called Perry to take her back to the hotel, where she was quarantined in her room.

Perry said that when he brought his mother back to the hotel, the room was a mess. His mother had also recently struggled to walk and get up from the bed. “She had went to the bathroom on the bed,” he said. “And I had to clean it up.”

Borrilez was more worried for her mother than ever. Living in Los Angeles, she felt powerless to help, especially when she couldn’t reach her mother for the next few days. It was unlike her not to answer her phone or call her back. Borrilez had previously worked in the Solano County Public Health Bureau, and called some of her old connections to check on her mother. At one point, a social worker slipped a note under her door at the Hampton asking Nicoletta to call her daughter.

Finally when Nicoletta called back, she said that she wasn’t feeling well but that program staff had done little for her. “All they did was come to my door and take my temperature and tell me not to leave my room,” Borillez recalled her mother telling her. “They don't do anything.”

But Borillez said she talked to her mother a few days after that and she sounded better. She said she still didn’t feel good, but Borillez was relieved to hear her sounding more energetic.

City records provided little insight into the program’s protocols when someone was quarantined with COVID.

Natalie Peterson, an analyst for the city of Vallejo, wrote in an Aug. 10, 2021, email to Solano County mental health services manager Miranda Ramirez, that there were three positive COVID cases throughout the program.

After consulting with Sharps, Peterson told Ramirez, who was seeking guidance on COVID isolation protocols, that “COVID+ individuals were sequestered to their rooms with meals left outside of their doors.”

On June 11, Nicoletta called Ashley Brackett, Perry’s longtime girlfriend, but Nicoletta said nothing and was moaning as if she was in pain. “I kept saying, ‘Cherie are you OK?’ and she kept moaning,” Brackett recalled in an interview.

Perry rushed over. “My mom called me and sounded in distress,” Perry recalled telling the security guard at the hotel. “I need to get up there to check on her.”

“They told me to come back on Monday because they can't do anything. They have to wait for Kevin [Sharps] to come back,” Perry said.

Perry repeatedly came back to the hotel over the weekend. At one point, Perry said that he spoke to a woman going door-to-door in the hall, who talked to someone downstairs and told Perry his mother was in the hospital, which wasn’t true.

On Monday morning, June 14, Perry was headed to work but decided to go back to the hotel and check, still hoping his mother was in a hospital.

As he walked into the hotel, he said he saw Sharps talking to a worker. When Sharps saw him, he said, “I'll let you in in a second” and told him to meet him at his mother’s door. When Sharps arrived, he used his key to immediately unlock the door.

“Are you ready for me to open the door?” Perry recalled Sharps asking him. Sharps let Perry walk in the room first, and he saw his mother lying on the floor, dead.

After that, he called Brackett screaming, “She’s dead” and crying, Brackett recalled.

A Vallejo police report indicates that Nicoletta had possibly been there for “a couple of days.”

“Who knows how long she would have been stuck up there if I didn't go there that morning to check on her?” Perry said.

In an interview earlier this year, Perry said he was still traumatized by the incident and had difficulty discussing it.

“I'm still recovering from it,” he said. “And I don't know if I ever will, because like I said, what's happened has happened, that's what happened to my mom, and I'm never gonna forget how it happened and how I had to go through all that.”

When asked about the deaths in the program, and specifically why it took so long to discover Nicoletta given that her son was trying to reach her, Colon Rivera said that Unity Care staff did not have any knowledge of such warnings.

“Unity Care staff did not work nights or weekends, so we have limited knowledge of what specifically occurred with respect to those residents,” Colon Rivera wrote in an email. “But I can say that no Unity Care staff was aware of Cherie Nicolette's death before she was discovered by Kevin Sharps and her son.”

City declares Project RoomKey a success

On July 31, 2021, six weeks after Nicoletta was found dead, Vallejo Mayor Robert McConnell posted an update on results from Project RoomKey on Facebook. He said that no participants were hospitalized for COVID-19. It is unclear if McConnell was aware of the deaths at the time.

“Unity Care case managers and staff have almost daily, certainly weekly, contact with most participants through meal, hygiene supply, and linen distributions and other structured points of contact to support engagement,” McConnell wrote.

At the termination of Project RoomKey’s contract in October 2021, the city hired a new provider, Shelter Inc. In December, city spokesperson Christina Lee told the Vallejo Sun that Unity Care “was not interested in continuing with the extension of the program and services, so the City was able to secure another provider to ensure that the continuum of care for the participants was uninterrupted.”

Project RoomKey’s funds ran out and the program officially ended last January, with the city providing some people space in temporary trailers and housing vouchers for hotels to others. The program is again managed by the Fighting Back Partnership, which is working with another nonprofit, 4th Second.

At a Jan. 11 City Council meeting, the first after the Vallejo Sun broke news of three deaths in Project RoomKey, several residents and Councilmember Cristina Arriola spoke about their concern with how people could have been left dead in their room for days.

City Attorney Veronica Nebb defended the city’s role in Project RoomKey by saying that its participants were “adults with rights.”

“We rented rooms for people,” Nebb said. “We didn’t knock down their doors if they didn’t answer them. We didn’t force them to interact with service providers. We gave them shelter, isolated them in a place where they weren’t as exposed to COVID, as they might have otherwise been and that was the extent of the program.”

Nicoletta’s remains were taken by the Solano County coroner’s office, but eight months later the investigation into her death remains ongoing. Borrilez said her mother was cremated and a memorial was held the following month at Northgate Christian Fellowship in Benicia.

“Life was not easy for her, but loving her kids unconditionally was,” Borrilez wrote in a Facebook post announcing her mother’s death. “She did her best, and now is free of the struggles and burdens of this life.”

Borrilez said she has mixed feelings: grateful that her mother was able to have a place to stay off the streets while also disturbed with the stories of dysfunction and neglect in Vallejo’s Project RoomKey.

“How can they know she is sick with COVID, yet leave her in a room for the weekend without checking on her wellbeing?” Borrilez said.

“I find it upsetting that funds were allocated to secure the safety net of this vulnerable population, yet they were placed in poor living conditions with what appears to be negligent care from whoever was supposed to help look after them,” Borrilez said. “I’m not saying it was all bad and I don’t know if it was out of carelessness, inattention, incompetence or all of those, but lives were lost and possibly unnecessarily.”

Clarification: This article has been updated to note that Unity Care surrendered its licences to operate foster care facilities after the state moved to revoke them.

Before you go...

It’s expensive to produce the kind of high-quality journalism we do at the Vallejo Sun. And we rely on reader support so we can keep publishing.

If you enjoy our regular beat reporting, in-depth investigations, and deep-dive podcast episodes, chip in so we can keep doing this work and bringing you the journalism you rely on.

Click here to become a sustaining member of our newsroom.

THE VALLEJO SUN NEWSLETTER

Investigative reporting, regular updates, events and more

- health

- Housing

- government

- homelessness

- COVID-19

- Vallejo

- Project Roomkey

- Hampton Inn

- Rodeway Inn

- Cheryl Nicoletta

- Robbie Perry

- Vallejo Police Department

- Kevin Sharps

- Unity Care

- Fighting Back Partnership

- Robert McConnell

- Tatiana Colon Rivera

- Department of Social Services

- Alyssa Borrilez

- Andre Chapman

- Gary Berg Jr.

- Angela Cook

- Tim Cook

- Six Flags Discovery Kingdom

- Margaret Morgan

- Shelter Inc.

- 4th Second

- Vallejo City Council

- Cristina Arriola

- Veronica Nebb

Scott Morris

Scott Morris is a journalist based in Oakland who covers policing, protest, civil rights and far-right extremism. His work has been published in ProPublica, the Appeal and Oaklandside.

follow me :