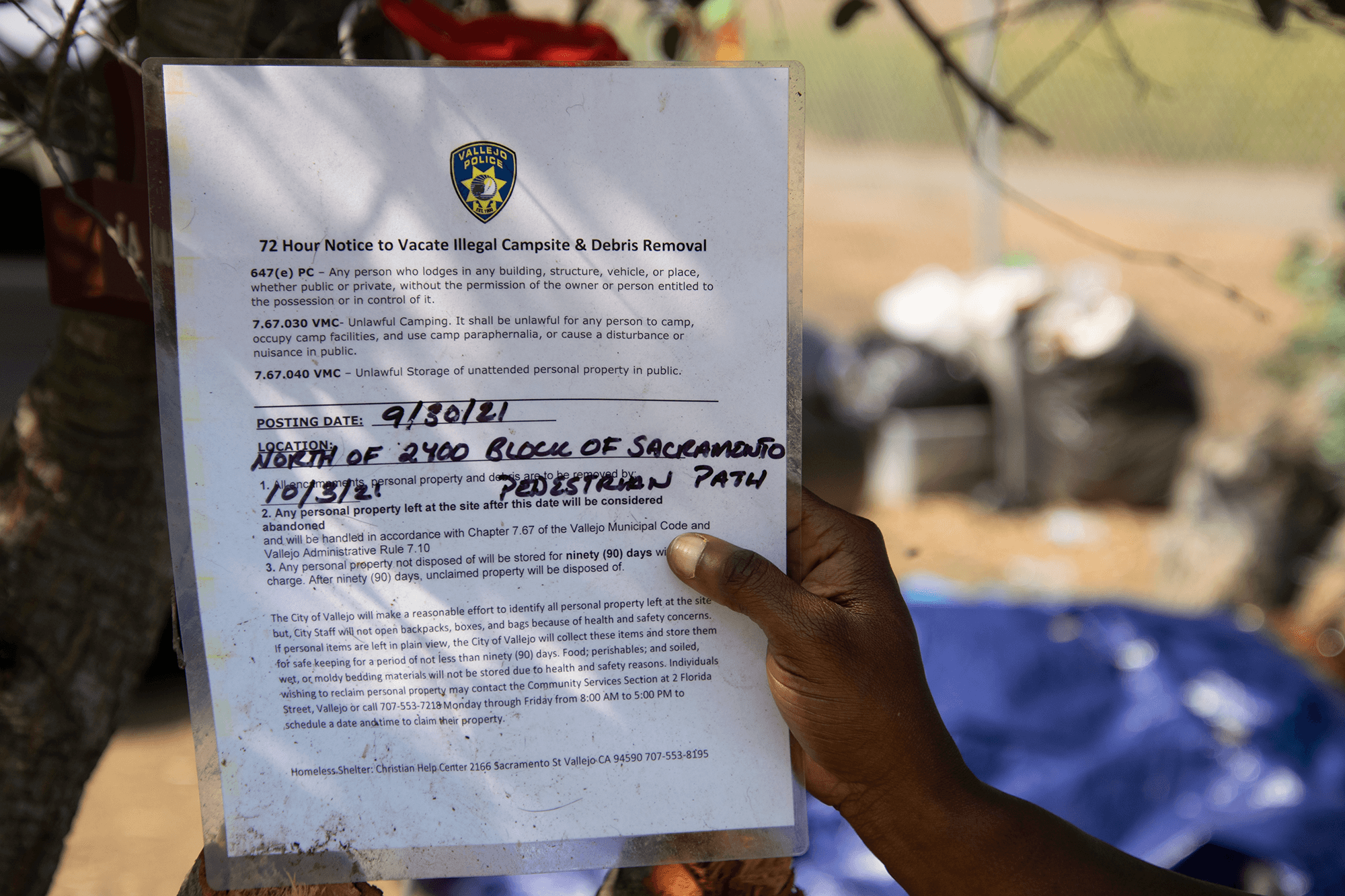

Mathew Evers tried to pack up his camp in north Vallejo before the bulldozers came. City workers had posted eviction notices in mid-September at the large homeless encampment near the Highway 37 overpass over Broadway, by a Recology facility and a tow yard.

Evers had been living there for nearly two years, left alone since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was hard to pull all of his possessions together and, while still packing, Evers said he fell asleep in a chair just before dawn.

At 7 a.m., a bulldozer wrecked everything Evers hadn’t packed into two shopping carts and a trailer. He said he lost thousands of dollars worth of possessions that day: fishing gear, a telescope, a computer, solar panels, batteries, bike parts, clothes, jewelry, eyeglasses, headphones, stereo equipment and more.

“And then I didn’t have anywhere to go. So I spent almost a week in hell on the street,” Evers said. “I was scared. I didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Evers estimates he’s been homeless for about eight years. He said he was going through a divorce when the housing market crashed more than a decade ago, and he couldn’t afford to pay for both his home and one for his ex-wife and children. So, he became homeless, yet he still worked and sent his earnings to take care of his children, who are now 18 and 27 years old, with one poised to become a doctor.

Evers is one of hundreds of people who live on the streets in Vallejo. Others like Evers say that their belongings are routinely destroyed, as the city evicts them from camps without providing a reasonable alternative.

There is little room in Vallejo’s only homeless shelter. Its Project Roomkey program to put people in hotels during the pandemic has been winding down for months. Promises of new resources, like a navigation center, have gone on for years with little progress.

Continually evicting people under such conditions could violate their Constitutional rights, said Osha Neumann, a civil rights attorney with the East Bay Community Law Center who has litigated homeless issues in California for decades.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2018 that cities cannot penalize people who cannot obtain shelter for sitting, sleeping or lying on public property. Neumann won a monetary settlement last year for people experiencing homelessness who had property destroyed by the state Department of Transportation in Oakland and Berkeley.

“Essentially, if you're homeless, your very existence is criminalized,” Neumann said, adding that many cities take what he calls the “leafblower approach to homelessness,” using police-enforced evictions to scatter people while offering few, if any, alternatives.

The most recent survey of homeless residents conducted in Solano County in 2019 found there were 1,151 people who were homeless and 81% – more than 900 people – lacked shelter. Half reported living in Vallejo at some point during the previous year. (The survey is typically done every two years, but was postponed in early 2021 because of concerns over COVID-19.)

Despite its sizable unsheltered population, Solano County only has three shelters: One each in Vallejo, Fairfield and Vacaville. The shelter in Vallejo, the county’s largest city, has fewer than 100 beds.

Still, Vallejo police often evict people experiencing homelessness, including those on private property. The property owners also face fines for not removing campers when the city says so. And people who have been evicted say their property is routinely destroyed, not saved or stored like the city says.

Brittany Jackson, a spokesperson for the Vallejo Police Department, did not respond directly to questions from the Sun about how frequently police enforce anti-camping ordinances. The city has not provided any records on evictions for seven weeks in response to a public records request.

Jackson said that the city stores property taken during evictions and offers counseling and shelter services on a bi-weekly basis. “The city complies with all local, state, and federal laws when noticing and prior to taking any action relating to illegal encampments,” Jackson said in an email.

Neumann said there may be a breaking point. “The people who are houseless themselves are going to begin fighting back and they are going to refuse to move when their stuff is taken,” he said.

That happened in Vallejo in October. After Evers was evicted from his last camp, he settled in another area near the same highway. But that camp also received an eviction notice last month. Evers and other residents organized a petition that argued that there was no room in shelters and they had no place else to go.

The police didn’t come. Seven weeks later, they’re still there.

COVID-19 opened more beds but not enough

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, it was clear that people without homes to shelter in – who often suffer from chronic medical conditions and live in congregate settings – were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. They wondered where they could go.

With that in mind, the state Department of Social Services enacted Project Roomkey, a statewide effort to provide spaces in hotels for people infected with COVID-19, exposed to COVID-19 or had conditions that put them at higher risk if they contracted COVID-19 and didn’t have housing.

In Solano County, Project Roomkey initially had locations in Fairfield, Vacaville and Vallejo. The Vacaville site, which had only 10 beds, closed two months later. The Fairfield site ended early this year. The Vallejo site, with about 80 beds at the Hampton Inn, remains open but is expected to close in the next few months.

Evers said that he spent about three weeks in a Project Roomkey hotel room, but it felt like “jail.” The program’s code of conduct required people to spend minimal time out of their rooms and be back by 10 p.m. Evers said he was tested for COVID daily, felt like “a guinea pig,” and had trouble coping with the isolation.

“No guests in your room. No phone in your room,” he said. “So many things went through your mind when you're isolated from everybody else for that long and it's hard. I couldn't do it.”

The Vallejo site’s funding has been precarious for months and has received extensions of one-time funds from both the state and federal government. Because of that, the city has not even filled the empty rooms it’s paid for.

“Vallejo has not been accepting new Project Roomkey [residents],” Deborah Vaughn, assistant director of Solano County Health and Social Services, said at a Sept. 28 Board of Supervisors meeting. “They’re open. They have an obligation for a certain number of rooms that have intentionally not been filled because they knew they were facing a wind-down of that program.”

The city of Vallejo said that its current Project Roomkey residents include 65 people staying in the Hampton Inn, and it’s working on transitioning them to permanent housing. It expects the program to conclude in January.

Vaughn said the program cost up to $650,000 per month to provide the required on-site meals, medical services, including behavioral health, and private security.

Some Project Roomkey funds are being diverted to hotel repairs

When the Solano County Board of Supervisors was asked to direct more than $1 million in state funds to Vallejo’s Project Roomkey site in September, Vaughn clarified that Vallejo hoped to use about half the funds to help pay the Hampton Inn for $900,000 in damages to the hotel.

“The hotel has sustained significant damages,” then-interim city manager Anne Cardwell said during the supervisors meeting. “Because it’s been full, we have not been able to address damages in rooms while participants are currently present."

Cardwell said that some of the repairs would include tearing out carpet and replacing mattresses, but the city did not provide the board with an itemized list of repairs, which troubled some supervisors.

“We’re being asked to allocate potentially a half a million dollars with nothing in front of us that says, ‘Here’s how it happened,’” Supervisor John Vasquez said. “It is a for-profit hotel. It does assume that it’s going to have some damages over time. It probably carries insurance for that."

Vallejo has provided no records itemizing the damages in response to a public records request the Vallejo Sun submitted on Oct. 12.

The county had hoped to put the full $1 million toward rehousing the people in Project Roomkey.

Less than one in five of the 316 people who left Project Roomkey ended up in permanent housing, while 10% have gone into temporary housing, Vaughn said. The county doesn’t know what happened to about 30 people who were once part of the program.

Vaughn emphasized that Project Roomkey was not an efficient use of funds for housing people, as it can cost more than $8,000 per participant per month, which could be spent on months of rent and food.

County supervisors are considering another source of funds to bolster the county’s homeless response: $86.9 million dollars from the American Rescue Plan Act. It’s still deciding how to spend it, but Supervisor Erin Hannigan suggested at a recent meeting that the county dedicate the money to combatting what she called Solano County’s “piecemeal approach to homelessness,” which she said is not only ineffective but limits the county’s ability to get more resources through grants and partnerships.

“It's successful in some ways,” she said, “but it doesn't take a person from homelessness in an emergency shelter all the way to permanent housing or possibly even a job or steady income.”

The county is conducting a survey until Nov. 30 on how to spend the ARP funds.

Few homeless shelters in Solano County. There often isn’t room for women, especially.

When the city of Vallejo posted eviction notices at the camp near Highway 37 last month, the notice referred people to the Christian Help Center, the city’s only shelter at 2166 Sacramento St., not far from the camp.

The center has been there for 40 years and has helped numerous people get off the streets and eventually find permanent housing, said Dr. Michael Hester, who sits on the center’s board.

The 100-bed shelter is available for anyone experiencing homelessness, if there’s a bed available, Hester said. Typically, he said, that would amount to 70 beds in the men’s dormitory and 30 beds in the women’s. But it has reduced its capacity to about two-thirds to enable social distancing during the pandemic.

As of late October, Hester said the center had 16 beds available in the men's dorm, but none in the women's dorm.

“The women's dorm tends to remain full because as soon as there's an opening and the women find out about it, they're there,” he said. “Obviously there's a safety issue and other issues for women, so that's never been a problem to fill the women's dorm.”

Hester said that there’s usually space available in the men’s dorm, though admittedly nowhere near enough for all the people with housing issues in Vallejo.

“People who would qualify to live there don't want to live there for one reason or another,” he said. "Some of these folks don't want to give up their drugs and we can't allow them to do drugs on the premises.”

But others may find the center’s rules or capacity too restrictive for their needs. Hester said that there is an 8 p.m. curfew, pets aren’t allowed, and people can’t bring in more than can fit in a locker.

“If someone's bringing in duffle bags full of things there is a problem with that,” Hester said, but there is some storage on site. The center would make an exception for the curfew if someone was working late but would need to be notified in advance.

“Clearly, we can’t operate a shelter without having rules,” Hester said, “but if people decide they're not willing to live by the rules, they're not a candidate to live at the shelter.”

Vallejo’s navigation center is years behind schedule and over budget

The city of Vallejo has promised to build a new homeless navigation center for years. The city council approved $2.3 million in U.S. Housing and Urban Development grants in May 2019, but more than two years later, there has been little progress and no timeline for its completion.

The city had promised that the center would be finished by the end of 2019 when it allowed people to camp in floodplains near Highway 37. But by December, the city evicted everyone there ahead of the winter and the navigation center was not finished. Some were temporarily placed in hotels.

In March of this year, housing and community development program manager Judy Shepard-Hall indicated that construction of the navigation center would begin in May so people could move in by the end of the year, according to a presentation obtained through a public records request.

On May 25, Shepard-Hall told the council that not only had the city not started construction, but the budget to build the center had ballooned from $4 million to $8.7 million. She also said that $1.3 million had been diverted to maintain Project Roomkey.

“I’m wondering if we had to put that in Project Roomkey because this didn’t move along,” Councilmember Mina Diaz said at the May 25 meeting.

Days later, Shepard-Hall was placed on leave, despite indicating during the meeting that she would return to the council with an update in July. Interim housing manager Gillian Hayes updated the Housing and Community Development Commission at its meeting earlier this month, saying the project still had a $2.3 million funding gap and was potentially years away from completion.

The city owns the land at 5 Midway St. and already bought prefabricated buildings to place on it. Three Solano-area hospitals – Kaiser, Sutter and NorthBay Medical Center – have committed a total of $6.2 million over three years for the center’s operations. But Hayes said that the city still lacks the funding to install the structures on the site.

Vallejo has also not been spending half a million dollars annually in housing assistance grants from HUD. In a Jan. 8, 2021, email, HUD community planning and development representative Chris Anderson indicated that the city had $500,000 in unspent HOME grant funds each from 2017, 2018 and 2019 and also had balances from 2015 and 2016.

In a statement, the city said that the unspent funds had been set aside for a development project, homebuyer mortgage assistance, rental assistance and other activities.

“These are slow-moving projects, and some have yet to be specifically identified,” the city said, adding that it will be amending its budget for HOME grants at the Dec. 14 city council meeting.

A place for people without homes to camp is hard to come by

The city of Vallejo can still evict people who camp with permission on private property. When a group camped on a vacant lot off Sonoma Boulevard next to Vallejo Furniture in August, the city of Vallejo code enforcement sent property owner Param Dhillon a letter, warning him of unauthorized camping. It threatened him with fines.

“I don't have any problem as long as they keep it clean, but they want me to do something to move them,” Dhillon told the Vallejo Sun.

Dhillon has been involved in a prolonged dispute with the Regional Water Quality Control Board and the city of Vallejo over his use of the land. Regulators say it’s a protected wetland, which Dhillon said isn’t true.

But when an atmospheric river brought heavy rains in October, Dhillon’s land flooded, sending the homeless residents scrambling to get out and find shelter wherever they could.

Some homeless advocates have pushed the city to establish a safe camping space. The city has promised to do so for at least a year, but it’s never identified a location.

Dionne Carter, executive director of Vallejo Together, a nonprofit that offers support services for people experiencing homelessness, said that her organization tries to offer services to people in encampments but that’s often difficult when the city continually moves them.

Carter said Vallejo Together asks the city to alert them to evictions so they can help move people. “But then again where can we move them to? That’s the question,” she said.

Carter said that a volunteer in her group took Vallejo Mayor Robert McConnell on a tour of Camp Hope in Martinez, a permitted homeless encampment operated by the nonprofit Homeless Action Coalition to provide services and stability to homeless residents. Carter said that Vallejo Together would like to do something similar and has discussed finding a location with the city, but it has been difficult to identify a space. (McConnell did not respond to a request for comment.)

“We’re looking for industrial or light industrial land because that can be zoned for encampments,” Carter said. Once they have a space, they’d like to build tiny homes and provide safe parking for people who live in their vehicles.

Hayes, the city’s interim housing manager, said at the last Housing and Community Development Commission meeting that the city is working on a “tent facility” that it hopes to open by January. In response to questions from the Vallejo Sun, Hayes said that the project is in the research phase and the city is working with nonprofit groups to find grants for funding.

But so far the city has not found any suitable locations. “The Housing Division took 12 potential locations to the City Council some time ago and Council did not approve any of the proposed locations for various reasons,” the city said in a statement in response to the Sun’s questions.

Federal appeals court rules criminalizing homelessness is cruel and unusual

Courts have held that cities can’t criminalize homelessness or destroy people’s possessions while cleaning up encampments. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the city of Boise, Idaho, could not enforce anti-camping laws if there was no shelter available, finding it violated the Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. The ruling affects the entire west coast.

“If you punish people for doing acts which they need for their survival, which they cannot help but do, that is cruel and unusual,” said Neumann, the civil rights attorney who has litigated homelessness cases in Berkeley. “It is like punishing someone for grieving.”

In addition, law enforcement actions against people experiencing homelessness often violate the Americans with Disabilities Act, because many of the affected people suffer from physical or psychiatric disabilities. “Disability is very, very prevalent in these communities of the unhoused,” Neumann said. “People often become homeless partly because of disabilities, including mental disabilities.”

In Solano County, 31% of homeless people surveyed in 2019 reported suffering from at least one disability, including 18% who suffered from a physical disability and 29% who suffered from a psychiatric condition.

But the ruling in Boise doesn’t stop police from contacting homeless people, just from citing or jailing them for being homeless. “The threat is obvious,” Neumann said, “a police officer with a gun and a club and the authority to take away your freedom. But as long as they don't actually cite you, at least as the courts interpret that, it's not a violation under Martin v. Boise.”

The government can’t, however, destroy property without allowing people to recover it. Neumann was part of a legal team who brought a class action lawsuit against Caltrans for destroying the property of people experiencing homelessness in Oakland and Berkeley. The suit alleged that Caltrans had destroyed valuable possessions and irreplaceable mementos like urns with ashes of loved ones, photos or lockets.

Last year, Caltrans agreed in a settlement to reimburse more than 1,000 people for destroying their property during encampment clearings. Part of that settlement requires Caltrans to abide by the terms statewide. But Neumann said that he’s been hearing reports of continued property destruction, including in Vallejo.

“The issue is basically a violation of people's 4th Amendment rights against unreasonable seizure of their property,” he said. “It is unfortunately all too common that people view the property of people who are homeless as garbage, just as they view the people themselves as garbage.”

Neumann only sees the problem getting worse because there aren’t enough homes for people who need them.

”As long as the government is not subsidizing housing, as long as the real estate market is in this bubble, as long as property is a commodity and not a right, we’re going to have homelessness,” he said. “We have increasing homelessness in this country and people need a place to go.”

Tracy Harris, a resident of the camp that resisted their eviction last month, said that she never recovered after her mother and 8-year-old son were stabbed to death in Fairfield in 1993. She wandered for years drinking and doing drugs and anything she could to block out the pain. She eventually returned to Solano County, where her sister and brother were also homeless, leaving them all with nowhere to turn for help.

“I take it day by day,” she said.

Harris says it’s hard to get help with the little income she can bring in once people hear two specific words: “homeless people.”

“Because they got better things to do than to deal with homeless people,” Harris said. “Because they downgrade us. It’s like we are a bad piece of meat.”

Before you go...

It’s expensive to produce the kind of high-quality journalism we do at the Vallejo Sun. And we rely on reader support so we can keep publishing.

If you enjoy our regular beat reporting, in-depth investigations, and deep-dive podcast episodes, chip in so we can keep doing this work and bringing you the journalism you rely on.

Click here to become a sustaining member of our newsroom.

THE VALLEJO SUN NEWSLETTER

Investigative reporting, regular updates, events and more

- Housing

- government

- policing

- Vallejo

- Mathew Evers

- Project Roomkey

- East Bay Community Law Center

- Osha Neumann

- 9th Circuit Court of Appeals

- Oakland

- Berkeley

- Brittany Jackson

- Deborah Vaughn

- Solano County Health and Social Services

- Solano County Board of Supervisors

- Hampton Inn

- Anne Cardwell

- John Vasquez

- Erin Hannigan

- American Rescue Plan

- Christian Help Center

- Michael Hester

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Judy Shepard-Hall

- Gillian Hayes

- Param Dhillon

- Camp Hope

- Robert McConnell

- Dionne Carter

- Vallejo City Council

- Regional Water Quality Control Board

- Tracy Harris

- Caltrans

- homelessness

- Vallejo for Racial Justice

- Vallejo Together

- Dale Matsuoka

- navigation center

Scott Morris

Scott Morris is a journalist based in Oakland who covers policing, protest, civil rights and far-right extremism. His work has been published in ProPublica, the Appeal and Oaklandside.

follow me :